In the three Burundian provinces of Mwaro, Muramvya and Gitega, community members are working together to invest in a collective vision of a more productive, sustainable and resilient landscape. For many communities, this involves capitalising on the untapped potential of bamboo.

The success of any community programme hinges on buy-in from the people who live in the area. Their participation in identifying challenges and finding long-lasting solutions is crucial. Sustainable solutions to human-centred challenges are only possible when the affected community supports and takes part in resilience building projects.

No one knows the land better than its own inhabitants. The RFS Burundi team, led by FAO, understand this, which is why the project promotes sustainable land management interventions that combine scientific practices and solutions with the indigenous knowledge of the local community members.

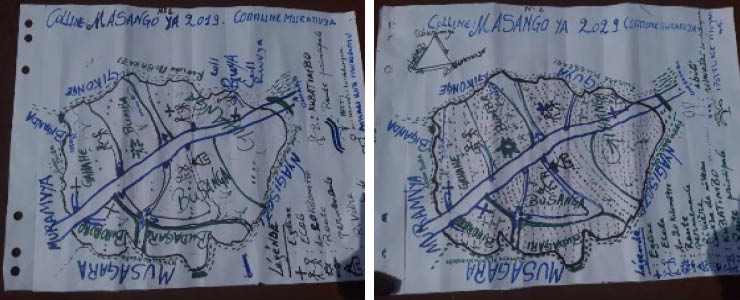

In order to incorporate local knowledge into sustainable land management, the project integrates participatory approaches into intervention design, implementation and monitoring. In Burundi’s Gitega, Mwaro and Muramvya provinces, this process starts with participatory community mapping of the surrounding landscape.

Participatory mapping is a well-established tool that helps capture and communicate community knowledge about local land use, land challenges and natural resource health. Communities first draw up a map that captures land boundaries, land uses, vegetation types, as well as the extent of land degradation, such as deforestation or the loss of soil fertility. In itself, this exercise is a valuable knowledge sharing opportunity. The act of collaborating to draw a collective map of the landscape builds awareness around land degradation issues and lays the groundwork for collective planning.

After agreeing on the current state of the landscape, the community is asked to think toward the future. What do they want their landscape to look like in ten years’ time? Through mapping their ideal landscape, community members start to develop a collective vision of the future, an important prerequisite to shifting collective understanding and values, particularly with regard to governance of natural resources.

“On the one hand, participatory mapping allows communities to make a critical analysis of their landscape, to draw up a list of prevailing socio-economic and ecological problems,” said Salvator Ndabirorere, RFS Project Coordinator, “and on the other hand, it allows communities to identify possible solutions for a better future for current and future generations.”

The next step? Turning that vision into reality. Through RFS, with support from the Burundian Ministry of Environment, Agriculture and Livestock, FAO supports communities in achieving their landscape goals. In areas where deforestation and soil erosion are rife, this means implementing anti-erosion approaches, such as agroforestry and contour planting, to stabilise the landscape and return nutrients and moisture back into the soil.

For communities along the banks of the Kayokwe, Mubarazi and Ruvyironza rivers, planting bamboo has proved to be one of the most successful approaches for combatting soil erosion and preventing landslides.

Bamboo is one of the fastest-growing plants on earth. With a strong root system that successfully holds topsoil, bamboo offers an ideal solution for halting erosion. In addition to stabilising the riverbank, bamboo improves water quality by decreasing sediment pollution.

As a high yielding plant, bamboo quickly improves the landscape’s capacity to mitigate climate change – it absorbs CO2 emissions better than other plants and produces 35% more oxygen than its green counterparts. Furthermore, it can be used as an alternative renewable biomass or biofuel, reducing pressure on remaining forest ecosystems.

Through Farmer Field Schools, communities in Burundi are learning innovative ways of growing bamboo in nurseries. In collaboration with the Provincial Office for Environment, Agriculture and Livestock, RFS has introduced culm-segment cutting to produce bamboo seedlings. More cost effective and productive that traditional reproductive methods of growing plants from seeds, culm-segment cutting involves growing bamboo from the stems of existing plants.

To date, 49,063 bamboo seedlings have been produced in nurseries and planted along the riverbanks. These plants protect roughly 150 km of land across three provinces. Along the banks of the Kayokwe River, fish species that had disappeared have begun to re-emerge.

The United Nations’ Africa Renewal magazine describes bamboo as a “new economic force” that has an enormous potential – not only to help with reforestation, but also to create jobs and generate an income for community members. Once harvested, bamboo has a plethora of commercial uses.

In Gitega province, women in the community are already transforming the bamboo into artisanal products sold at local markets to generate additional household income. “Bamboo plays a significant economic role in communities,” said Mr. Ndabirorere. Bamboo stems are used for constructing enclosures, building houses and stables, making beehives for beekeeping and decorating houses and tourist sites in urban areas.

Burundi is growing its own future, one bamboo plant at a time.

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter to receive updates on stories directly from the field across all our projects, upcoming events, new resources, and more.